What is Meniere’s Disease?

Meniere’s disease is a disorder of the inner ear, which causes episodes of vertigo, imbalance, fluctuating hearing loss, pressure in the ear, and tinnitus (noises) in ones ear. An episode of Meniere’s disease can last for minutes, up to many hours in duration.

Meniere’s disease most often affects only one ear and often individuals will perceive a change in hearing, increased pressure in the ear, or tinnitus in one of their ears prior to an episode of vertigo. Due to the prolonged nature of the vertigo it is also not unusual to have significant nausea, sweating and vomiting with an episode.

Terminology

To better understand Meniere’s disease one should also understand the common terminology. Dizziness is a word used to describe a number sensations including: lightheadedness or a near-faint sensation, disequilibrium or imbalance, disorientation, and vertigo. A sensation of vertigo is a type of dizziness, where one feels a false sense that either they or their environment is in motion, when they are in fact stable.

With Meniere’s disease, the vertigo is spontaneous, meaning that the individual did not do anything to bring on the symptoms and there is nothing that can be done to cause this sensation to cease. Tinnitus refers to a perceived noise that one is actually hearing, but this is not due to a sound in the external environment. Tinnitus is most often a side effect of hearing damage and can present as a variety of sound including: ringing, roaring, humming, buzzing or even cricket sounds.

Origins of Meniere’s Disease

This disorder was first described by a French physician, Prosper Meniere in 1861, at a time in which vertigo was primarily thought to be caused by disorders of the brain rather than the ear.3

He theorized that the episodes were actually caused by fluctuating inner ear function and were not related to abnormalities of the brain. This greatly changed the way that physicians viewed and treated patients with vertigo.

Functions of the Inner Ear

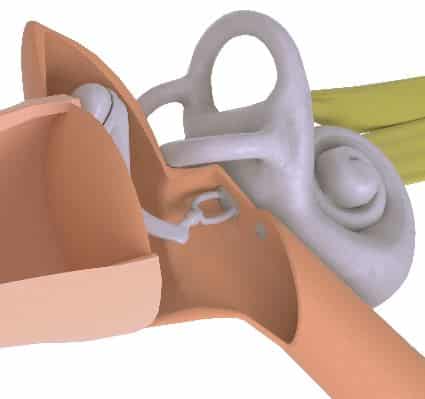

The inner ear is not only involved in hearing, but the vestibular system contributes to our sense of balance and equilibrium

The inner ear has two primary functions, the sensation of hearing, as well as contributions to balance and equilibrium. The cochlea is the organ of hearing and allows for perception of sound. The vestibular organs are the part of the inner ear that sense head movement and send reflexive signals to the eyes and lower extremities as part of the vestibular system.

The vestibular system allows for stable vision with head movement, as well as reflexive postural control. The entire inner ear is filled with fluid, with a membranous separation of the two primary inner ear fluids, called endolymph and perilymph. Both systems have microscopic hair cells that respond to fluid movement within them. The primary function of the hair cells is to transform the fluid movement in the inner ear into electrical energy to be sent to the brain for perception.

Potential Causes of Meniere’s Disease

Meniere’s disease is a diagnosis based off of symptoms and a clinical pattern of test findings. With that said, there is general disagreement on the exact cause, or more likely causes, of Meniere’s disease. It has long been known that those with Meniere’s disease have poor regulation of an inner ear fluid called endolymph.15

Sometimes the term ‘endolymphatic hydrops’ and Meniere’s disease are used interchangeably, with the term ‘hydrops’ simply referring to an over-accumulation of fluid. This abnormal fluid regulation is thought to cause a build up of fluid pressure inside of the inner ear. There have been theories proposed that the excess fluid could be caused by an over production, under absorption or poor draining of the endolymph. At this time the abnormal fluid regulation is not fully understood and is likely caused by a number of factors.6

Meniere’s disease is diagnosed based on symptoms and clinical test patterns, but the exact cause remains uncertain, leading to debates. Poor regulation of the inner ear fluid, known as endolymph, is a common characteristic, and the condition is sometimes interchangeably referred to as ‘endolymphatic hydrops,’ suggesting an abnormal fluid buildup that might be caused by multiple factors yet to be fully understood.

Traditional Views on Meniere’s

Initially, it was thought that endolymph levels fluctuated. If the endolymph levels increased, this would exert more pressure on the inner ear. The increase in pressure within the inner ear was thought to stimulate all of the cochlear and vestibular sensors simultaneously in one ear, thus causing the episode of vertigo, fluctuating hearing, tinnitus, and pressure in the affected ear.

The sensation of vertigo was thought to be generated due to the disagreement between the ears from the increased fluid pressure in the affected ear. Anytime the inner ear vestibular organs disagree on the amount of stimulation, this leads to a jerking eye movement called nystagmus. The nystagmus with this disorder causes the sensation of vertigo.

It was thought that, over time, the fluid levels would recede, reducing the pressure exerted on the cochlear and vestibular hair cells. The reduction in pressure exerted on the ear was thought to lessen the symptoms of tinnitus, pressure in the ear, decreased hearing, and vertigo. This more traditional view of Meniere’s disease is likely flawed though, as more recent studies have shown that there are individuals with Meniere’s disease without endolymphatic hydrops and individuals with endolymphatic hydrops without Meniere’s disease.6,8,12

It was thought that, over time, the fluid levels would recede, reducing the pressure exerted on the cochlear and vestibular hair cells. The reduction in pressure exerted on the ear was thought to lessen the symptoms of tinnitus, pressure in the ear, decreased hearing, and vertigo. This more traditional view of Meniere’s disease is likely flawed though, as more recent studies have shown that there are individuals with Meniere’s disease without endolymphatic hydrops and individuals with endolymphatic hydrops without Meniere’s disease.6,8,12

Despite the disagreement, it is generally accepted that most individuals with Meniere’s disease do have endolymphatic hydrops, but it may be a side effect of the disease process and not the cause of the symptoms.6,12

Other Possible Theories

There are also theories that Meniere’s disease could be related to autoimmune inner ear response, allergy, trauma, abnormal endolymph ionic makeup, viral infection, genetics, trapped otoconia (inner ear rocks), related to migraine, and/or related to poor blood flow to the inner ear.6,12,16

In recent years, there has been more focus on migraine and Meniere’s symptoms. Several studies have shown that there is significant overlap between the symptoms of vestibular migraine and those of Meniere’s disease. Researches hope that a deeper understanding of the connection could lead to improved treatment approaches for both conditions in the future.

Who is affected by Meniere’s Disease

Meniere’s disease is not thought to be common, with recent estimates showing that it affects 0.2% of the population.1 Meniere’s is most often diagnosed in individuals between the ages of 40 to 60.2

In general, it seems that both males and females are equally likely to develop Meniere’s disease. There are some studies showing that Meniere’s disease primarily affects Caucasians;5 however, at present there is not enough evidence to support a strong racial correlation. It seems likely that genetic factors do in fact play a role in some individuals with Meniere’s disease, but due to the large number of potential causes for the condition, it is unlikely to be attributed to a single genetic factor. There is some evidence that those with a prior history of head injury or whiplash injury may be at increased risk for developing Meniere’s disease.7

Meniere’s disease is rare, affecting 0.2% of the population, usually diagnosed in individuals aged 40 to 60. It is equally likely to occur in both males and females, and while genetics may play a role, its cause may be influenced by various factors, including a history of head or whiplash injury.

Long Term Course of Meniere’s Disease

Meniere’s disease usually only affects one ear, but long-term studies show that the other ear can be affected in almost 50% of cases. Even when the disease does affect the other ear, for most the symptoms are less severe.9 Generally, the episodes of vertigo associated with Meniere’s disease decrease in the frequency and severity within 5-10 years of onset.9

How is Meniere’s Disease Evaluated and Diagnosed?

There is not a specific test for Meniere’s disease, but experts in the area have some general recommendations in order to make the diagnosis.

The expert panel recommends two categories for the diagnosis:

- Definite Meniere’s disease, and

- Probable Meniere’s disease

For a diagnosis of definite Meniere’s disease, an individual should have episodes of vertigo for 20 minutes to 12 hours, with documented low-frequency (low-pitch) sensorineural (inner ear) hearing loss in the affected ear. Also, there should be fluctuating hearing, tinnitus, and/or a pressure sensation in the affected ear.

The category of probable Meniere’s disease is broader and requires episodic dizziness symptoms associated with fluctuating hearing, tinnitus, and/or pressure in the ear, lasting from 20 minutes to 24 hours.10

In the assessment of Meniere’s disease, obtaining a detailed and thorough record of ones symptoms is essential. Careful consideration should be made to what symptoms go along with the episodes of dizziness. At a minimum a subjective report of ones symptoms and a hearing evaluation should be completed, in attempt to document hearing loss in the affected ear. The pattern of low-frequency (low-pitch) sensorineural (inner ear) hearing loss in the affected ear is not typically seen with other inner ear disorders, and is essential to the diagnosis of definite Meniere’s disease.

In the early stages of Meniere’s the hearing in the affected ear typically decreases with the episode of vertigo and often will return to normal shortly after the episode. If possible, documentation of fluctuating low-frequency sensorineural hearing loss in the affected ear is extremely helpful, as there are many things that can causes ones hearing to decline, but relatively few things that will cause the hearing to fluctuate in this manner. With repeated attacks of Meniere’s disease, both the cochlear and vestibular hair cells become damaged. This results in more permanent hearing loss, tinnitus, and aural pressure that become more pronounced with the episodes.

Symptoms of vestibular deficit following repeated episodes can include imbalance that is made worse when walking in scenarios with poor lighting or on uneven ground. Also, an individual left with vestibular deficits may experience occasional disorientation with head or body movements.

Other helpful tests for the diagnosis of Meniere’s disease to document vestibular damage include a battery of tests, such as:

- VNG or (videonystagmography),

- Rotational chair,

- Video head impulse test (vHIT), and

- Vestibular evoked myogenic potential (VEMP)

With the above mentioned combination of tests, the entire peripheral vestibular system can be assessed. However, many of these tests are not routinely performed in clinics due to the costs of equipment and training of the staff.

Due to the difficulty distinguishing Meniere’s disease from Vestibular migraine, in our view, it is helpful to complete vestibular testing because repeated attacks of Meniere’s disease will leave vestibular damage, while testing in vestibular migraine is usually normal. Also, in more recent years there have been brought forward specific patterns of vestibular test findings that are often observed in patients with Meniere’s disease, allowing for more certainty in diagnosis.11

In the past a test called electrocochleography (ECOG) was also frequently utilized for those with suspected Meniere’s disease, as this test allows for the detection of endolymphatic hydrops. To rule out other potential causes of a patient’s symptoms, cranial imaging and blood tests may also be performed.

Management of Meniere’s Disease

Managing the symptoms of Meniere’s disease involves addressing both the intense vertigo episodes and the time between them.

During an Episode

The vertigo associated with an episode of Meniere’s disease can be extremely intense, leading to nausea and vomiting. Medications to manage nausea and vestibular suppressants are often prescribed for use during an episode. If one is unable to stay hydrated due to the vomiting, admission to the hospital may be required for intravenous fluids.

The vertigo associated with an episode of Meniere’s disease can be extremely intense, leading to nausea and vomiting. Medications to manage nausea and vestibular suppressants are often prescribed for use during an episode. If one is unable to stay hydrated due to the vomiting, admission to the hospital may be required for intravenous fluids.

To reduce the severity of the dizziness, it is generally recommended that one lie down on a firm surface and remain as still as possible. Due to the disagreement in vestibular input to the brain during a Meniere’s attack, any movement can make the sensation of vertigo more intense. Also, if possible, staring at a stationary object can reduce the nystagmus and thus the sensation of vertigo associated with the episode. However, some individuals are unable to do this and may need to just remain motionless with their eyes closed.

Between Episodes

Meniere’s disease is typically treated by an Otolaryngologist, a medical doctor with specialty in disorders of the ears, nose, and throat. Due to the disagreement on the cause of Meniere’s disease, treatments vary widely, as does the effectiveness at controlling the symptoms.

Because of the variability in treatments, we will only discuss those most frequently utilized. In most instances, Meniere’s disease is initially treated conservatively with treatments that have a low risk for side effects.

Some of the typical first line treatments include dietary changes, such as reducing one’s salt, alcohol, tobacco, and caffeine intake, as well as reducing stress. Some individuals are also placed on a diuretic (water pill), in attempt to reduce fluid accumulation in the body.

These treatments have varying levels of effectiveness but are relatively benign and are effective for some with Meniere’s disease. If the initial treatments are ineffective, steroids may be administered. Steroid treatment for Meniere’s disease can include oral steroids, but they may also be injected into the middle ear space. Steroids have been shown to reduce the frequency of episodes for some individuals with Meniere’s disease.13

If the steroids are ineffective, then more aggressive treatments are explored. A procedure injecting powerful antibiotics into the ear, thus damaging the hair cells in the ear, can reduce the severity of the episodes of vertigo.4 With this treatment there is a small risk of permanent hearing loss,4 but a high likelihood of at least some degree of permanent vestibular deficit.

There are also surgical procedures to promote drainage of endolymph from the inner ear, as well as procedures that cut the vestibular nerve.14 Any surgical procedure has risks associated with it, and with some of these more aggressive treatments, individuals are often trading the recurrent attacks of vertigo for some degree of permanent disequilibrium. However, for those who are debilitated by the disease, some of the more aggressive treatments are effective and can provide some relief from the intense episodes.

References

- Agrawal, Y., Ward, B.K., & Minor, L.B. (2013) Vestibular dysfunction: Prevalence, impact and need for targeted treatment. Journal of Vestibular Research. 23(3): 113-117.

- Alexander, T.H., & Harris, J.P. (2010) Current epidemiology of meniere’s syndrome. Otolaryngol. Clinics of North Am. 43(5): 965-970.

- Baloh, R. (2001) Prosper Meniere and his disease. Arch. Neurol.. 58(7): 1151-1156. doi:10.1001/archneur.58.7.1151

- Cohen-Kerem, R., Kisilevsky, V., Einarson, T.R., Kozer, E., Kore, G., & Rutka, J.A. (2004). Intratympanic gentamicin for Meniere’s disease: a meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 114(12): 2085-2091.

- Chiarella, G., Petrolo, C. & Cassandro, E. (2015) The genetics of menieres disease. The Application of Clinical Genetics. 8:9-17.

- Cureoglu, S., Costa Monsanto, R., & Paparella, M. (2016) Histopathology of meniere’s disease. Oper Tech Otolayngol Head Neck Surg. 27(4): 194-204.

- DiBiase, P., & Arriaga, M.A. (1997) Post-traumatic hydrops. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am.. 30(6): 1117-1122.

- Honrubia V. (1999) Pathophysiology of meniere’s disease. Meniere’s disease (Ed. Harris JP) 231-260 Pub: Kugler (The Hague).

- Huppert, D., Strupp, M. & Brandt, T. (2010) Long-term course of Meniere’s disease revisited. Acta. Otolaryngol.. 130(6): 644-651.

- Lopez-Escamez, J.A., Carey, J., Chung, W.H., Goebel, J.A., Magnusson, M., Mandala, M. …. & Bisdorff, A. (2016) Diagnostic criteria for Menière’s disease. Consensus document of the Bárány Society, the Japan Society for Equilibrium Research, the European Academy of Otology and Neurotology (EAONO), the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) and the Korean Balance Society. Acta Otorrinolaryngol. 67(1): 1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.otorri.2015.05.005.

- McCaslin, D., Rivas, A., Jacobson, G., & Bennett, M. (2015) The dissociation of video head impulse test (vHIT) and bithermal caloric test results provides localization of vestibular system impairment in patients with “definite” Meniere’s disease. American Journal of Audiology. 24: 1-10.

- Merchant, S.N., Adams, J.C. & Nadol, J.B. (2005) Pathophysiology of ménière’s syndrome: Are symptoms caused by endolymphatic hydrops? Otology & Neurotology. 26: 74-81.

- Miller, M. & Agrawal, Y. (2014) Intratympanic therapies for Meniere’s disease. Curr. Otorhinolaryngol. Rep.. 2(3): 137-143

- Silverstein, H., Smouha, E. & Jones, R. Natural history vs. surgery for meniere’s disease. Otolaryngol. Head & Neck Surg.(1989) 100(1): 6-16.

- Yamakawa, K. (1938) Temporal bone histopathology of meniere’s patient. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting Oto-Rhino-Laryngol Society; Japan.

- Yamane, H., Sunami, K., Iguchi, H., Sakamoto, H., Imoto, T., & Rask-Andersen, H. (2012) Assessment of Meniere’s disease from a radiological aspect – saccular otoconia as a cause of Meniere’s disease?. Acta. Otolaryngol.. 132(10): 1054-1060.

Brady Workman, AuD, is an audiologist in the Balance Disorders program at Wake Forest Baptist Health Center. He has authored several articles relating to balance and vestibular disorders as a regular contributor and co-editor of the Dizziness Depot at Hearing Health & Technology Matters. Brady received his doctorate of audiology from East Tennessee State University in 2018 and is licensed by the North Carolina Board of Examiners for Speech Language Pathologists and Audiologists and is a fellow of the American Academy of Audiology.